It is so that the images brought to mind by Mark’s Gospel today are gruesome in the extreme. Perhaps because of or in spite of this, one almost cannot help but be pulled into the drama playing out before us now where the scene includes:

- A drunken party

- A young girl’s (no doubt) provocative dance

- A booze-induced, pride-filled, careless promise

- A bitter grudge

- An underling who must not/cannot see that he has a choice

- A ghastly head on a platter

- And the final, only apparent act of dignity: the releasing of his body for burial.

The scene we are forced to step into now is all too real and so very heartbreaking and what is particularly heartbreaking, it seems to me, is that it is not difficult at all to imagine the same playing out today. Indeed, how often do we see precious human beings being portrayed as somehow ‘less than human’ even as they are used as pawns in larger dramas induced by pride or corruption or greed? How often do we see the tragic ending of John lived out in individuals and in families even now?

Is it any wonder that when Jesus receives news of this that he urges his closest followers to a quiet place by themselves for a while? Is it any wonder?

For there is very little goodness and surely not much justice to be seen today.

Except for maybe this:

The fact that Herod is utterly transfixed by John not only in life, but also in death. In fact, one might even argue that John holds even more sway over Herod after he met the sword, for he is utterly outside Herod’s control now. Indeed, might this small thing point us to this truth that there are, in fact, powers greater than the earthly ones we often cannot imagine overcoming? That maybe holiness and righteousness will one day have the last say? Indeed, even Herod seems to acknowledge that there are eternal consequences for such as this as he surmises that somehow “John has been raised.”

And yet for all of this, I struggle to understand why this gruesome interlude is included in Mark’s telling now. Unless…

Maybe it is so that this is shared simply so that you and I have a sense of what finally did happen to John. Maybe it is a way of ‘closing the loop’ on one who was important to the story we receive and share. (As in, ‘whatever happened to John?’)

Or maybe it is to show us that people — particularly people in power — are taking note of Jesus. Perhaps this is a turning point in the story itself when we hear that Herod is wondering.

Or maybe it is included just to hold up a mirror to us all so that we do not forget that:

- When earthly powers are understood to be limitless;

- When human pride holds sway over our better instincts;

- When some human beings — as surely must have been the case with John — are considered to be of less value than others;

This is how it ends.

Only it doesn’t end there, does it?

For Herod cannot forget it. It won’t let him go.

And you and I surely have not forgotten — neither John nor what became of him. In fact, this is a story which has resonated in art across the centuries.

And Herod’s confusing Jesus with John does not stop the teaching and the healing and the dying and the rising and the living which will follow. To be sure, this is but one small awful episode in a drama where in the end all that is good wins.

And yet, I cannot help but think today that this is small comfort to the thousands upon thousands who have been crushed by the likes of Herod then and now.

And so it is that for now, at least, I am doing all I can to experience this story as a mirror so as to more clearly see and understand what can happen next when:

- earthly powers are understood to be limitless;

- and human pride holds sway over our better instincts

- and when some human beings are considered to be less valuable than others…

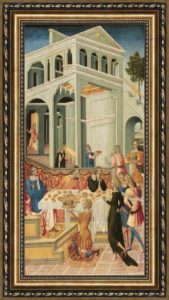

Oh, it might be easier not to, of course. For instance, take a look at Giovanni di Paolo’s rendition of the scene painted in the mid-fifteenth century. (Six such scenes from John’s life are part of the permanent collection at the Art Institute of Chicago which I was privileged to see a few days back.) I am especially struck by the fact that Herod’s guests cannot bear to look at John’s head on that platter. In di Paolo’s interpretation, even Herod himself recoils at the result of his own command to execute John. And yet, as awful as it is, we dare not cover our eyes.

For I am surely convinced that even this awful footnote in the story of Jesus broke the very heart of God. As it still does whenever and wherever the ‘Herods’ of this world do the same and innocents suffer for no good earthly reason. And if God’s heart is broken, then so must ours be. And if our hearts are broken, then we can’t be still, can we? And perhaps if we cannot be still, in some small way that is surely Good News that we are privileged to experience and share today. What do you think?

At least this is how I am led to experience this story this time through. If you want to see how I grappled with it in seasons past, you can go to my previous blog posts:

And so I wonder now…

- What do you make of the story of the beheading of John? Why do you think Mark includes it in his Gospel telling?

- Does it make sense to you to experience this story as a means to show us the ways and places where such as this happens still? Why or why not?

- If this does make sense, where do you see this happening today? How might you use such examples to help others see that this isn’t some ancient happening, but is as current as this morning’s headlines?

- Where do you see Good News in the telling of this story? Is it in Herod’s inkling that there are greater powers than even him at work? Is the Good News finally lived out in our unwillingness, our inability to ‘be still’ in the face of such as this? Is it somewhere else? What do you think?